The Little Museum of Dublin is a warm portrayal of Dublin through the years of the 20th century, as the Irish nation geared up to and grappled with its new-found status as a Republic. Uniquely for a museum, many of the photographs and memorabilia that constitute the exhibits themselves are sourced from local residents of Dublin who themselves lived or had immediate ancestry experiencing the years the Little Museum covers.

Something of a hidden gem of Dublin, the Little Museum is located in what first seems an ordinary, patrician Georgian house on St. Stephen’s Green. Within however exhibitions on a variety of themes, be it Dublin during wartime or the Irish capital’s portrayals in film, liven the museum regularly. Despite only having opened its doors in 2011, the Little Museum of Dublin’s inclusive approach to imparting knowledge has won it awards, with the Irish Times famously lauding the place as “Dublin’s best museum experience.”

The National Museum of Ireland is split between four distinct departments – three are in Dublin, while a fourth – the Museum of Country Life – is aptly located in County Mayo. The various artistic and scientific achievements of the Irish peoples and natural beauty of the Irish nation are heralded within each respective building, with the general foundation of the museum’s dating to the late 19th century.

Given the volume of exhibits and donated materials the National Museum’s founding society were receiving year on year, the expansion to different buildings assorted by Art, Archaelogy and Natural History was inevitable. The results are plain to see today – entire structures stocked with the pick of the finest and most interesting inventories, with new exhibitions regular across all of the departments. Examples include a modern history focus upon founding of the Irish Republic, and ancient history as with exhibitions of Clontarf and Medieval Eire. Best of all, entry to any of the museum’s displays is completely free.

The Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA) is situated in Dublin’s Royal Hospital Kilmainham, itself a fine example of 17th century architecture. The artistic displays are complimented by the museum’s well-sculpted gardens and verdant lawns, with a wholesale restoration of the premises having taken place during the 1980s. A few years after the hospital building was brought back to glory, the decision was taken for this ideal structure to host some of the finest modern art in the world.

Having been the epicentre of Dublin’s modern and postmodern artistic display for well over two decades, the Irish Museum of Modern Art offers those interested in perusing the representative installations and wall-mounted works a serene, whitewashed environment in which to contemplate these creations. The yearly exhibitions concerning famed figures in modernist art keep the museum’s galleries in a state of constant refresh.

Glasnevin Cemetery is the final resting place for well over a million people, and serves as something of a historic marker for a series of events to have befallen Ireland over the past two centuries. Prior to Glasnevin Cemetery’s establishment, there was no place for Catholics in Ireland to bury their deceased, which restricted the proper putting to rest of individuals according to that faith’s traditions.

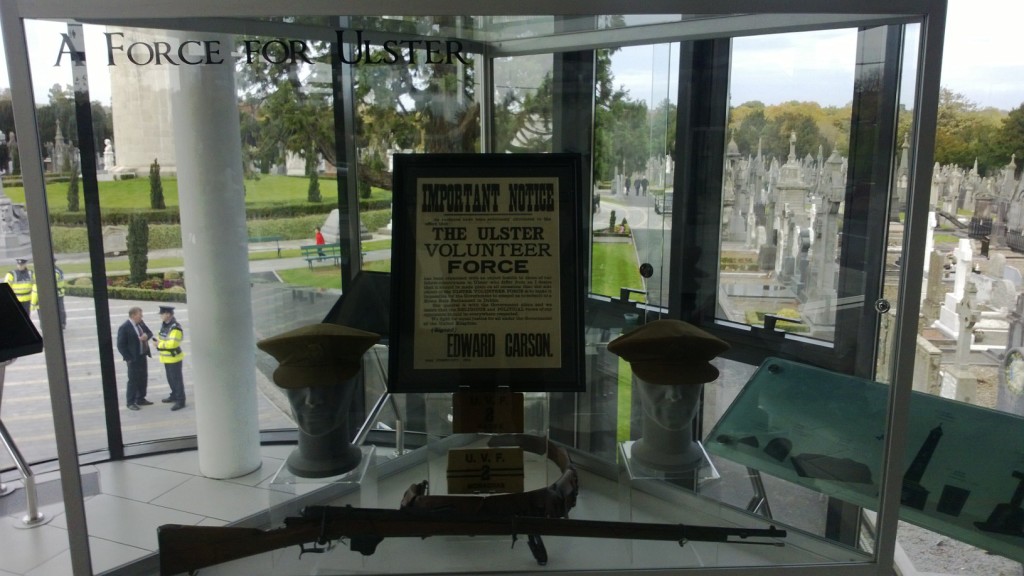

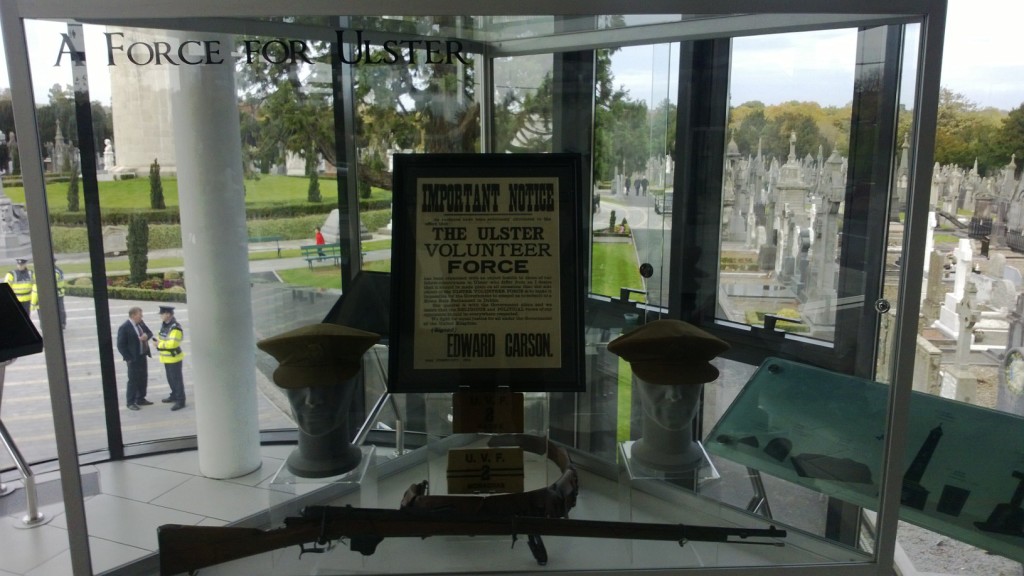

Glasnevin is one among very few cemeteries to have the distinction of its very own museum, its rich association with Ireland and Dublin history paving the way for displays chronicling how times effected change as ever-growing numbers of departed passed into Glasnevin’s grounds. Within the fields themselves, several notable tombs and sepulchres properly commemorate the distinguished and historic people resting there. Until his death and burial at Glasnevin Cemetery in 2014, historian Shane MacThomais served as its chronicler in chief.

The Jeanie Johnston Tall Ship and Famine Museum is situated around the ship itself, its purpose being to inform visitors about the vessels which played a crucial role in helping Ireland’s native population emigrate in the face of the widespread and devastating famine of the 1840s. The project was conceived in the late 1980s, with the Jeannie Johnston laid down in 1998 after painstaking research into the appearance of the original 19th century vessel.

Given how dramatic, frenetic and historic the hastily arranged emigrations were, the remade Jeannie Johnston serves as a living recreation of the conditions the Irish of that harsh era had to endure and withstand. A simple number speaks volumes: the ship was designed to carry a mere 40 people including, however on one voyage a total of 252 people managed to pack aboard in order to reach foreign shores.